|

|

|

|

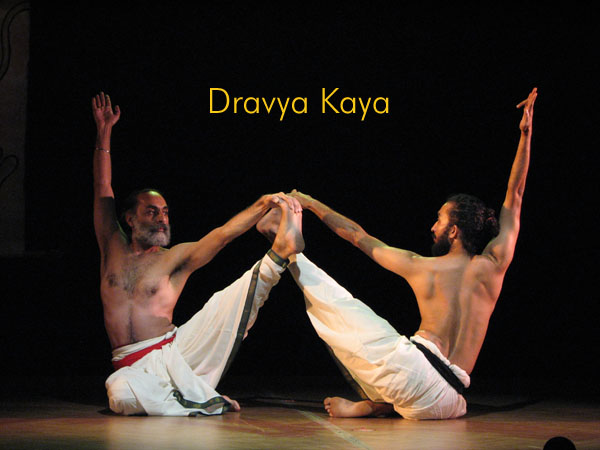

Choreographer’s Note: A section of Dravya Kaya was first made for the Natya Kala Conference at the Sri Krishna Gana Sabha, Chennai, in December 2008; the theme of the conference was "Ramayana." Ever since 1992, when a mob of Hindu rightwing rioters demolished the early 16th century, Barbari Masjid, claiming that the mosque was built upon the historical site of Rama’s birth, I had desisted dancing Rama-centric pieces for fear of being seen to be endorsing the fundamentalists. In fact, one of my teachers from Kalakshetra even exclaimed, "Aiyo! Now how can we dance and sing praises of Rama ever again?" Apart from the obvious political reasons for which I and millions of others were outraged, the thing that disturbed me deeply about the fundamentalists was their need to pull Rama into the realm of the tangible by pinning down his birth to a physical site. To me, characters like Rama (and even Ranjha whom I explore in my other work, Fana’a: Ranjha Revisited) are fluid entities who lie fully ensconced in their poetic realities that run parallel to ours and which we may freely tap into at will. They are there because of the poetry that they inhabit and which conversely engulfs and constructs them. They and their poetic narrative are one, and in turn their poetic universe significantly informs our sense of self. Rukmini Devi used to say that Rama and Sita belong to every Indian, and even though such a statement might seem politically problematic today, there is truth to it; I can definitely say that they deeply inform the Hindu and Sikh psyche. We may choose to celebrate them, emulate them, or even challenge them, but they remain primary reference points and abiding cultural archetypes for us. Thus, Dravya Kaya is an attempt to reclaim Rama—the cultural archetype—from the clutches of Hindutatva, and this I decided to do through the neutral agency of props and objects found in the Ramayana. If I were not a dancer, I would be a designer. I am fascinated by shape and design of objects and am curious of how inanimate objects dictate movement and engagement. I also find it extremely fascinating that objects that surround us help in telling our story. They are not just inanimate things but signifiers in themselves, signifying us and our times, so they are silent repositories of our biographies and the historical contexts that we inhabit. In Dravya Kaya, or quite literally Object-Body, I explore how an object attracts attention, offers direction and elicits movement and engagement. Thus exploring the epic drama one property at a time: bamboo, bark, earth and rock, but with an eye on the social and political reality as it implicates Rama today.

Credits: Choreography: Navtej Johar ALMOST

A TOUCH kodanda

rama, gambhira rama — Moving

ever-so gently, diagonally towards each other, Your

outstretched hands, the two dancers’ finger-tips You

depict the story of Ram’s bow – kodanda, of

Sita’s disrobing — sari’s

endless unwrapping — Bamboo,

bark, earth, rock — elements that construct stopping

just before the nail-tips feather-touch. You swan-swim with a dancer bearing my name, For

Review click: http://www.narthaki.com/info/rev09/rev780.html |

|

![]()